At a lecture presented at the University of Oxford’s renowned Sheldonian Theater, Grameen Bank’s founder, Professor Muhammad Yunus, stated that “not only is poverty the most pressing issue of our time…it is [also] a problem that we have fully the capacity to tackle and overcome within the first half of the century---

if we choose to do so.” The greater industry of microfinance has evolved from pockets of small-scale programs of limited scope to a diversified and dynamic one that engages several actors in the innovation of more effective methodologies, products, and services to better serve the poor. During my time in Bangladesh, I had the opportunity to visit both Grameen Bank and BRAC’s programs at the field level to gain a better understanding of their approaches in practical terms.

Grameen Bank

Poverty is not a symptom of the poor but rather an outcome of social and economic policies borne out of existing institutions and frameworks. The current banking system is one such financial institution, and as Yunus mentions, is fundamentally flawed when it excludes more than half of the world’s population because they are not deemed credit-worthy. The Grameen Bank was established to develop a banking method which can deliver financial services to those left out of the formal system, particularly women, whom are hardest to reach in most of the world.

I won’t go into the details of the Grameen methodology, structure, and financial products and services here. There are numerous online publications detailing these topics, including the

Grameen Bank’s official website. Of Grameen’s 8 million borrowers, 97% are female. Loans are made without guarantees, collateral, or tedious paperwork, however, generally, clients are required to be members of a registered group of 5-10 like-minded individuals who are not blood-related, share a common level of education, are permanent residents of the same village, and are landless*/assetless. Functioning primarily on an honor-based system, Grameen permits a great extent of flexibility on loan repayment schedules without charging penalties, and as of 2008, its repayment rate stood at 98%. An internal survey demonstrates that clients are steadily crossing the poverty line each year with 64% of borrowers, who have been members for at least 5 years, having already crossed the poverty line.

The general structure of Grameen Bank is a hierarchical one, which follows: group → center → branch → area office → zonal office → head office in Dhaka. During my field visit, I visited a center-level meeting for income generation loan clients and the branch office and met with the area office manager in order to get a brief exposure to the most grassroots segments of the structure.

The center level meeting was comprised of approximately 8 groups and was held in a tin structure constructed for the purpose of such weekly meetings. The clients we met were all women, and most were engaged in the business of selling gold scraps stripped from coal to jewelers. During the center meetings, clients engage in loan repayments and weekly savings depositing, followed by requests for new or supplemental loans. During the latter, all members of the applicant’s group must be present and affirm that the purpose and amount of the request is valid. The center head’s opinion and approval is also sought, particularly on the applicant’s ability to repay the amount requested. Within the subsequent week, the branch officer presiding over the meetings conducts her own due diligence of the applicant. The request, if approved, is then proposed to the branch manager, who conducts additional due diligence before approving and sharing with the area manager for approval. Once the application is approved, the branch officer prepares the amount for disbursement, and the applicant is notified at the subsequent center meeting that her loan amount is ready for collection. The repayment schedule, distinguishing principle and interest, is shared with the client at the time of collection to ensure that she is aware of her repayment requirements and options.

Grameen clients gather for the center meeting in Dhumrai

Grameen clients gather for the center meeting in Dhumrai

Husbands of the clients contributing to the gold stripping process

Husbands of the clients contributing to the gold stripping process

Clients deposit their weekly savings and loan repayments during the center meeting

Clients deposit their weekly savings and loan repayments during the center meeting

Vehicles could not transport us to the site of the village and the center meeting venue. From the nearest village, we were required to walk a few kilometers before hiring a villager to transport us the remainder of the way on something similar to a rickshaw. We were visiting a center hardly considered remote, presenting just a sliver of the effort Grameen has taken in bringing banking to the poor.

Village children playing with an abandoned fishing boat

Village children playing with an abandoned fishing boat

is the world’s largest NGO, initiated from Bangladesh and now, with offices throughout the world. The agency is also renowned for its work in microfinance and its integration with enterprise development. DABI for poverty alleviation for poor, landless women and Unnoti, providing enterprise development support for marginal farmers, are based on a group lending model, whereas Progoti, which provides enterprise development support for micro and small entrepreneurs, relies on an individual lending model. This integration of microfinance with technical support, provision of high quality inputs, and marketing is called a credit-plus approach and demonstrates a more innovative way of making access to finance an effective tool to bring people out of poverty.

I spent more of my time focusing on the organization’s Ultra Poor Program, which aims to reach the poorest within communities in Bangladesh. Though the program is grant rather than credit-based, it addresses the larger question of how to serve the poorest of the poor. At present, most microfinance programs target those lingering around the poverty line (a little over $2 per day) and assume that those well below the poverty line ($1.25 per day) are not capable of making credit a productive asset to create a diverse set of income generation sources for themselves. This group, with BRAC and other agency support, are proving otherwise.

The income of the ultra poor is even more irregular than that of the poor, and expenditure for matters of survival other than food is zero. Income is generated from begging and most often generated by children of school-going age. After a series of social mapping and grading of solvency, households are selected to participate in the program, through which they receive vocational and other training in income generation activities, assets to engage in the activity, a daily allowance and healthcare to facilitate their success, and ongoing mentoring for up to three years. To complement this, beneficiaries’ communities are mobilized to form poverty alleviation committees to ensure that community members are more intimately involved in the program and are motivated to provide their support to ultra poor members. This understanding nurtures more intimate relationships among the community members and creates a sense of responsibility and achievement as communities, as a whole, are uplifted.

Actors within Bangladesh have made great strides in addressing poverty through innovative means. Their success has spurred inspiration and replication of similar programs throughout the world. When I received a call from Grameen Foundation USA offering me a position with their Solutions for the Poorest unit while I was coincidentally visiting these initiatives, it seemed to be destiny, and I accepted. This month, I will start working with the unit to design and execute pilot programs testing the “downscalability” of integrated and value chain approaches of microfinance and enterprise development. We will start in India, and when successful, will expand this mission on a global scale. A choice has been made, and the journey finally begins.

*landless = less than 50 decimals of land

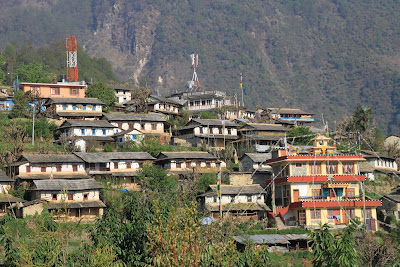

View of Annapurna range from my Landruk guesthouse

View of Annapurna range from my Landruk guesthouse